Q: We haven’t spoken of social work yet or its impact on your writing.

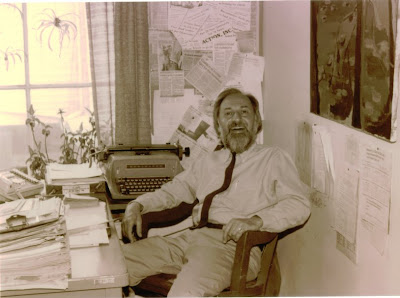

A: The thirty years I spent as a social worker and Director of Advocacy & Housing at Action, Inc.,

At the same time, while writing in At the Cut about my own childhood experiences-the discovery of sexuality, deceit, betrayal, the unuttered family stories of my friends, the insidious nature of gossip-I began to understand what Olson had meant by the “secret history” of a town or city. I realized that there were at least two competing narratives about my hometown. One was the conventional surface story of the great if decaying seaport and its heroic fishermen, who braved all odds to bring their catches to port. This was the narrative of tourist brochures and of Kipling’s sentimental Captains Courageous. It was the story the city told to itself and to those we wanted to entice here, the story we shared to make ourselves feel part of the

The other narrative was the one I had actually been living as I grew up in

Q: Do you think you have succeeded in writing that secret history?

A: I’ve barely scratched the surface; and the living and writing I’ve done here up to now have only served to show me how little I know about

Q: What do you propose to do about this?

A: I’ve begun another novel about

Q: And what about your own personal story?

A: I’m trying to continue the story of my own education and growth in a sequel to At the Cut, which I’m calling “After the Cut.” This, of course, will be a memoir. I also hope to complete a sequel to No Fortunes that will be based on my experiences in

Q: Did you come of age politically in

A: I arrived in

Q: Be more specific.

A: I was in love with a young woman named Rita, who came from the

It was the time of the Algerian uprising, when the French “paras,” who’d been sent in to quell the insurgency, the violent demonstrations, and to frustrate further anti-colonial actions, began to perpetrate unconscionable brutality on the indigenous population. Petitions were being signed all over Europe against the French response to

One day Rita and I were alone. We’d taken a walk along the

“I like you, Pietro,” Rita said. “And I enjoy spending time together. But you remind me of myself when I was in liceo. We’re miles apart politically, and you’re still very young emotionally.”

Q: Do you suppose the differences she was getting at were more of a cultural nature?

A: To some extent, I think. But the Italian students I met were quite mature; and they were very serious, serious about their studies and serious about politics, about the world. I was serious about literature, about things intellectual, but in retrospect it’s clear to me that I didn’t know how to be in a mature relationship. And I was in kindergarten politically. I’d never really thought through the myths we were conditioned to accept in school and college; you know, that the

Q: That was a turning point for you?

A: It was the turning point. After the horror-the obscenity of our actions in Vietnam, the secret wars we waged in Laos and Cambodia, the napalm, the burning of villages, the massacre at My Lai of women and children by American soldiers, the lies about the body counts and about our reasons for intervening-I never felt the same about my government again or about America. You can imagine how I feel now with the country engaged in yet another illegal and unnecessary war, fought by working class kids, Latinos and Blacks; a war which we lied our way into and which is turning the rest of the world against us. Talk about déjà vu.

Q: What happened with Rita?

A: She broke up with me. We saw each other from time to time, but it was clear she’d drawn a line. Then I stopped going to class so I could have more time to write. I was teaching at night, so I wanted the day time for writing. I also wanted time for travel and for exploring the vast treasure house of Florentine art. But the fact of the matter was that I needed to grow up. I needed to grow up emotionally and I needed to come to some mature understanding of political life, especially if I wanted to write.

Q: That apparently didn’t happen until you returned to

A: It didn’t. In fact, it took several more years until I was smack in the middle of the antiwar movement as a graduate student, when my former wife and I began attending demonstrations and going to teach-ins, really at her urging because she was far more politically engaged than I was. That’s when I started reading the major political and social texts of the 19th and 20th century, Marx, Engels, Bakunin, Kropotkin, Lenin, Trotsky, Edmund Wilson’s To the Finland Station, C. Wright Mills’ critiques of American capitalism, and of course all of Herbert Marcuse’s books. For years I hardly touched contemporary fiction or poetry. All I read was history and politics. I had to teach myself everything I hadn’t learned about the world as a liberal arts student during the Cold War—everything that had been withheld from me by my teachers.

It was the most profound education of my life, this reading of Thorstein Veblen and Randolf Bourne, of Georges Sorel, of Gunnar Myrdal’s An American Dilemma, Adorno’s The Authoritarian Personality, Ray Ginger’s masterful biography of Eugene Debbs. I immersed myself in everything from Schlesinger on FDR to Deutscher on Trotsky. I scoured the major books on the Russian Revolution, from John Reed’s Ten Days that Shook the World to Adam Ulam’s The Bolsheviks. I read Henry Adams on the degradation of democratic dogma and Julian Benda on the betrayal of intellectuals. I read Bertrand de Jouvanel and Ronald Sampson on the nature and psychology of power, Elias Canetti on crowds and power, and Hannah Arendt on totalitarianism. Then I turned to Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks. I even read Erich Hoffer’s The True Believer. I wanted to explore all sides, take in all views, though what drew me principally were the texts on the Left. I read most of the major American proletarian novels along with Rideout’s The Radical Novel in the United States and Daniel Aaron’s comprehensive Writers on the Left. I studied the Sacco and Vanzetti case, and I read the Lynds’ book on

Q: What was the result of all this reading, this study?

A: I emerged in the 1970s as a very different person, and, I believe, a more thoughtful one, though not an ideologue. Ideology of any stripe is anathema to me. I’m as suspicious of its temptations—and its excesses—as I am of religion’s. I no longer viewed the world through purely literary eyes, no longer trusted anything on its face. I’d finally become a skeptic, which is what my teachers at Bowdoin had always exhorted us to become. But most of all, I came away from my reading in history and politics with a profoundly tragic view of life. What I’d only understood intellectually from studying Shakespeare and the Greeks, that life is essentially transitory in nature and human beings seem doomed to repeat their mistakes, I now experienced viscerally. I’d become a pessimist. It’s difficult for me not to believe that human beings seem hell bent on destroying our species or the planet that sustains us, and I have little hope for any change in the trend.

Q: No wonder you couldn’t write fiction!

A: I’ve never thought of it that way, but I suppose my immersion in the reality of war, the history of violence and class struggle, diverse and often competing theories of self and society, or of the individual and government, provided me with a very different world view. It was a sobering one, as I’ve said, and, quite frankly, the fiction I later tried to read by John Updike or Ann Beattie seemed rather thin and silly, irrelevant, in a word, though I enjoyed returning to Mailer, especially his journalism; and there was some Vonnegut that was meaningful to me. I also read Pyncheon, while catching up with Bellow, Malamud and Roth, all of whom were as vital to me as Kerouac and Burroughs had been earlier.

Q: Who are the writers most important to you now?

A: There are many, among whom I would name Richard Yates, whose Flaubertian technical mastery has been a huge source of instruction and inspiration to me. Revolutionary Road is one of the essential American books. I came late to Yates, as I did to writers like John Fante and Edward Lewis Wallant, whose differing realisms have been important to study, along with Suttree and Blood Meridian, by Cormac McCarthy. I found Blood Meridian as penetrating a novel about the American soul, and as innovative in language and conception, as Moby-Dick.

All during the 70s and 80s I read backward and forward, from

Q: Is there anyone else?

A: There are many more writers. Echoing Melville, Olson always said that he read in order to write, and I suppose it’s been the same for me. I didn’t mention Henry Miller, whose autobiographical narratives have helped me think about how to use myself and my own experiences in my writings, and whose Tropics inspired me to live in

But the writer who has meant the most to me, and still does, is D. H. Lawrence. I don’t write like Lawrence and I don’t agree with a lot of his thinking; but ever since I began to read Lawrence in college I have been drawn to the life of this quintessentially British working class intellectual, who was able heroically to transcend home, class and culture. I wrote my senior thesis on The Plumed Serpent, and over the years I have read and re-read his novels. I’ve also read all the major biographies and critical studies. No one in 20th century fiction grasped the sense of place quite as well as

Writers are compulsive readers. We never cease rummaging around in books. I never know who is going to put the next revelatory text in my hand, or where I will find a review that will send me to my computer to order the book. Just this week I’ve been reading Patrick Cockburn’s memoir of surviving childhood polio in Ireland; and all summer I’ve been immersed in Ingeborg Bachmann and Ewe Johnson, who take me back to the post-war Europe I inhabited as a student. So it never ends, this restless reading, this desire to learn, to know more, to know how people live and how they think about what happens to them. And, of course, to write my own versions, based on what I myself have experienced.

Q: You’ve spoken about fiction. What role has criticism played in your writing life?

A: Criticism has played an extremely important role in my reading and writing life, indeed in the life of my mind. Ever since I heard John Aldridge deliver a stunning talk on the role of the writer in the university at a literary conference held at Bowdoin in the fall of my freshman year I have been reading criticism. Until I’d heard Aldridge speak I hadn’t read much literary criticism or even thought about it as a separate genre. I began by reading two books by Aldridge that had recently been published, After the Lost Generation and In Search of Heresy: American Literature in an Age of Conformity. I can’t begin to describe the impact of those books on me. In fact, it can be said that if anything helped me decide to become a writer it was reading Aldridge, who had written so poignantly about what it meant to be an American writer, first in Paris in the 1920s, when he focused on Hemingway, Fitzgerald and other members of the Lost Generation, and then in post-war America, in his no less powerful chapters on Mailer, John Horne Burns, Vance Bourjaily and Gore Vidal. Aldridge gave me American writing as it was then being practiced, more directly than from any course I might have taken; and he also gave me the first means I had of evaluating that writing. After reading Aldridge I went on to read Malcolm Cowley’s Exile’s Return, his first-hand report on the Lost Generation, and then Cowley’s The Literary Situation, about writing and publishing at mid-century. From Cowley I moved on to read Edmund Wilson’s literary criticism (it would be some years before I found To the Finland Station and Patriotic Gore). By sophomore year I had begun to read formal criticism of a more academic nature in my literature courses; and then I took a year-long seminar in the theory and practice of criticism. But it was Aldridge who got me started, and I have been reading criticism ever since, not only for what I can learn from it about writing, but also because I find the best criticism incredibly stimulating on a purely intellectual level.

Q: Do you see a role for criticism today?

A: Informed and well-written criticism, like

Q: Where do you see yourself as a writer--in what tradition or school?

A: I suppose I might call myself a social realist, though I have come to this place through an absorption in Modernism. My earliest stories were experimental, influenced first by Faulkner’s time and point of view shifts or Dos Passos’s collages, and then by the French nouveau roman writers Natalie Sarraute, Alain Robbe-Grillet and Claude Simon. Reading Evergreen Review in college opened me to much of the new post-war writing in

But the more I wrote, I seemed to write my way out of an overt or willed experimentalism, in which I’d hide my story or attempt to tell two or three stories simultaneously. After a while I got tired of the kind of game playing that seemed de rigueur by the 1960s, culminating in the novels of Rudolph Wurlitzer or the stories of Donald Barthelme. The editors who rejected my work must have too! So I began again by telling simple stories. My first two novels had been heavily influenced by Pavese’s, in a reversal of his own pattern of having been inspired by Hemingway and Sherwood Anderson. But even underneath my experimental fiction there had been a discernable floor of reality, of the concrete: real places, real people, real events, real time. And that emerged even more as I moved between memoir and fiction.

Q: What is your relationship with these two genres?

A: As I’ve evolved as a writer these are the two principle ways I write, the main poles of my expression. I suppose I have two stories I want or need to tell. One is the story of my life as it actually happened, or at least as I remember its happening, in the places I grew up in, among the people I came to consciousness with. The other is a larger story, in which I also figure. It’s the story of our times, of the era I have lived through and the places I’ve lived, few as they may be; along with the events and ideas that have defined us. I have needed fiction to tell this other story because it goes beyond my own actual experiences. I have needed to create characters, to embellish events I may or may not have participated in, places I haven’t seen. I have had to be liberated from myself and my own experiences in this telling beyond memoir or autobiography. And for this reason I have come to fiction.

In each case the autobiographical figures. In fact, it could be said that I have tried to find two ways of writing about myself, one real, the other imaginative, though there is some necessary crossover, perhaps even some intentional blurring of categories or distinctions, although I will leave that to others to decide. My models in this work have included Henry Miller, Jack Kerouac and Charles Bukowski, among Americans, and Proust, Celine and Thomas Bernhard among Europeans. But the primary thrust has been to find compatible ways of telling those two crucial stories, which are the only ones I know, the only ones I have an interest in telling, or an ability to relate.

Q: You’ve mentioned Charles Olson so often. Have you had other mentors.

A: Olson was probably the most significant figure in my life. He was the person, who, by his own example, allowed me to be myself. But there were also some teachers who were extremely important to me in high school and college. One was Hortense Harris, who trained two generations of writers at

In college, novelist Stephen Minot, was my freshman English instructor and he also taught the advanced writing courses. I’ve never had a better writing teacher than Steve, or anyone who encouraged me more in the kinds of writing I wanted to do, especially fiction and the personal essay. By far my best literature teacher was critic and PEN-Faulkner Prize winning novelist Lawrence Sargent Hall. Larry’s course in the British Romantics was not only my introduction to the sublime poetry of Wordsworth, Coleridge, Shelley and Keats; it was also my initiation into formal literary criticism, which I continued to pursue with Larry in seminars I’ve mentioned in the theory and practice of criticism and contemporary literature. I’ve written elsewhere about my philosophy professor, Walter Solmitz, who taught us philosophy by showing us how to philosophize. Holocaust survivor, master teacher and wise friend, Walter personified the type of European intellectual that I have always admired and wanted to emulate.

Besides these invaluable teachers, I’ve had two other significant mentors. One is Vincent Ferrini, the poet I’ve already spoken of, who, at 94, is still my friend and going strong as a writer and gadfly to the city. It was Vincent who introduced me to contemporary poetry when I was a teenager, giving me Pound and Williams to read and offering the kind of conversation I’d only dreamed of having up till then. He was my first example of a committed writer and he never ceases to amaze me with his open-mindedness.

My other mentor—and he’s still a valued friend with whom I correspond regularly—was the novelist Peter Denzer, whom I met in

Most important, Peter, who’d been a foreign correspondent and, as an infantryman, was present at the liberation of

Q: We’ve spoken about the imaginative writers who have influenced you; and you’ve mentioned your reading in history and politics. Which philosophers have been important to you?

A: While there have been many thinkers I’ve read both in class and on my own—Plato, Aquinas, Kant, Schopenhauer, Hegel, Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, and later, Bergson, Husserl, Jaspers, Whitehead, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, Günter Anders, and Ernst Bloch—there is one who has had the most impact on me, and that is Sartre. I began reading Sartre my first year in college, starting with the novels, Nausea and the Chemins de la Liberte’ trilogy. Then I read, not always comprehendingly, Being and Nothingness, and later Search for a Method and Critique of Dialectical Reason. I’ve also, and very slowly, been working my way through The Family Idiot series on Flaubert. But what has been most important to me about Sartre is his life of activism, his political stance, or rather, stances, over the years. Sartre has been a singular example to me of the intellectual life, a model of how to think and act on one’s principles and beliefs. He has been the public intellectual I’ve most admired and wanted to emulate. Metaphysics has interested me less than ontology; and of all the schools of thought I’ve been exposed to existentialism has meant the most to me. Its insistence on how to live in a world of doubt and despair, in the absence of credible belief or ideology, in the midst of the unfolding of one tragic event after the other—indeed, in the unbelievable folly of our times-has made it the most relevant account of who we are and what we can do with our lives. While I’ve also read in analytical and cognitive philosophy and, most recently, in George Lakoff’s philosophy of the embodied mind, I’ve yet to be inspired the way I was inspired by my first readings in Sartre and Camus. They spoke to me out of their varying and often oppositional views on the human condition in a way that no philosopher has spoken to me since-at least any that I’ve discovered. They helped me to understand that this is the only world we have or will have. And we are condemned to make our own way in it. This is both our burden as human beings and our freedom. We make of it what we will.

Q: Do you read any science?

A: Not as much as I’d like to, though now I’m trying to catch up with the new thinking about the brain and the cognitive process, so I’ve been reading Kenneth Edelman, Steven Pinker and Daniel Dennett, among others. But long before I began to read literature I read in science. My early memoir Siva Dancing details that first passion of mine, when I was in seventh and eighth grade and I actually thought I might want to become a scientist. I had my own “laboratory” in the basement of our house on

Q: You’ve mentioned jazz and your brother who was a musician and composer. How important has music been to you?

At the same time I was deepening my knowledge of jazz and contemporary music through the wonder of long-playing records. But the biggest influence on my musical education was a college classmate, Bob Mettler, who had a spectacular collection of jazz and contemporary classical and avant-garde recordings. It was Bob who introduced me to the music of Bartok and the

After college my brother and I upgraded our hi-fi to a full-stereo system and added considerably to our growing record collection, which included the major bebop and hard bop artists, beginning with Diz, Bird and Miles, and moving on through the Horace Silver quintets, as well as small mainstream groups and big bands, expanding in the 1960s to encompass avant-garde musicians like Archie Shepp, John Coltrane, Albert Ayler and Ornette Coleman. I also began purchasing the latest recordings of Bartok’s Quartets and the

Not a day goes by in which I don’t listen to some form of music, though my preference is for the experimental—and I might add that, aside from the pleasure I take in music, it’s also been very important to my writing. I have come to see prose as having a musical dimension, both structurally and emotionally, and I’m constantly striving to incorporate that into my writing.

As I've said about writers, I could spend hours talking about the painters and paintings that have excited and influenced me, but let me limit myself to an essential few. In Gloucester it was my friendship with the Paris-born, Yugoslavian painter Albert Alcalay, whom I’ve written about elsewhere, that opened me to American Abstract Expressionism, which had the greatest impact on me of any visual art. I suppose that when we are young there are certain essential experiences in the arts, in music and literature; and my experience of the paintings of Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline and their contemporaries was singular, in the same way that my experience of existentialism in philosophy or High Modernism in literature was. Somehow after that, contemporary painting seemed tame to me, though I have come to enjoy a whole range of new art in the years since I first looked at the work of de Kooning and Motherwell.

In Europe I came to love the work of abstractionists like the Spanish painter Antonio Tapies, or the Italians, Burri, Afro, Scanavino, and Vedova; but, interestingly, it was the work of two figurative, though expressionist, painters that influenced me the most—John Bratby in England and Renato Guttuso in Italy. Each in his own way did something innovative with the human figure, with people and landscapes, both exterior and interior, that no one in

Aside from the aesthetic, the sensual pleasures, that we get from music and the visual arts, they also help to train our intellectual and artistic sensibilities. They teach us how to see and how to listen—how to look and feel, and how to express those discoveries. I don’t believe I could write without either, nor can I imagine a life without the joys of painting and music.

Q: What role have your children played in your life?

A: There’s a maxim that says we eventually end up learning from our children, and that is certainly true for me. My son Jonathan, now 41, has been a Socratic figure in my life since he was a teenager, forcing me to examine every premise of my politics while teaching me about popular culture, the media, and how to live practically in the world. Rhea, my daughter, who’s an art historian, has led me through the intricacies of recent art and the critical discourses through which it is understood; while her twin brother Ben, author of three published novels, has been both an inspiration in his own fiction and criticism and a sensitive reader and critic of my work.

Q: And your parents?

A: My father died in 1975 at the age of 75, followed by my brother, in 1977. Tom was 37, a marvelous jazz musician and composer. His death and my father’s were a turning point in my life, forcing me to confront my own mortality. My mother, who suffered from dementia, spending eight years in a nursing home, died on December 10, 2005. She was 95.

When we’re younger it’s often easy to blame our parents for our disappointments or failures, or to believe we were misunderstood by them. But in retrospect, my parents, with their immigrant values of self-reliance and self-improvement, were powerful role models for me of how to live one’s life responsibly and productively. Beginning when we were toddlers, my mother read to us nightly, instilling in us a lifelong love of books. Even when he was on the road, living out of cars and buses for months at a time, Tom always carried a book with him; and he’d write me letters about what he was reading-the stories of Hemingway and Fitzgerald, Liddell Hart on the Second War. It was Tom who first introduced me to the writings of Hunter Thompson.

More important, my parents believed in the value of an education. There was never a question about going to college. Higher education was simply assumed in our family, in contrast to many of the families of our friends, who felt that attending college was a waste of time. While they had some initial qualms about Tom’s becoming a jazz musician and my desire to write (like many immigrant parents they hoped that college would lead not merely to a good job but to a profession), our parents were ultimately very supportive. They traveled to

Q: Are you pleased with your life? Have you achieved what you set out to accomplish?

A: I’m as happy as one can be in a time of violence and mendacity, a time when so many of the humanistic values I believe in are being undermined by the forces of ignorance, superstition and greed-and by an Administration, headed by a person of unutterable mediocrity, that has brought us as close to fascism as we’ve ever come in America. I’m pleased with the achievements of my children, and I’m grateful to be sharing my life with a wonderful woman, who has been my partner for twenty years. As for having achieved what I set out to accomplish, I’d have to say that I’ve fallen far short of the mark I set for myself as an undergraduate. But maybe our youthful dreams are just that, a function of our idealism and our inexperience, and as we live we adjust to the shifting reality of our situations. At this point in my life, I have everything in place to do the work I want to do. I’ve had an excellent formal education, beginning in the

Q: Finally, what do you want for yourself now?

A: I want time, time to read the books that still beckon to me, time to reflect, time to spend with the woman I love; time, too, for grandchildren, now that I have my first, Ben's son Isaac. And I want time to write. I feel I’ve just begun and already I’m pushing 70.

September 3-9, 2005

(Revised April 10, 2007

No comments:

Post a Comment