Peter Anastas

St. Peter’s Fiesta, which opens its 88th year with music on Wednesday, June 24, at St .Peter’s Park and concludes on Sunday night, June 28, with a procession through the Fort, is Gloucester’s most meaningful celebration of our collective identity. Watching the lights and the altar go up this week and feeling the excitement in the air of impending carnival, which so many of us have experienced since childhood, I couldn’t help but remember the first time I took my grandson to Fiesta…

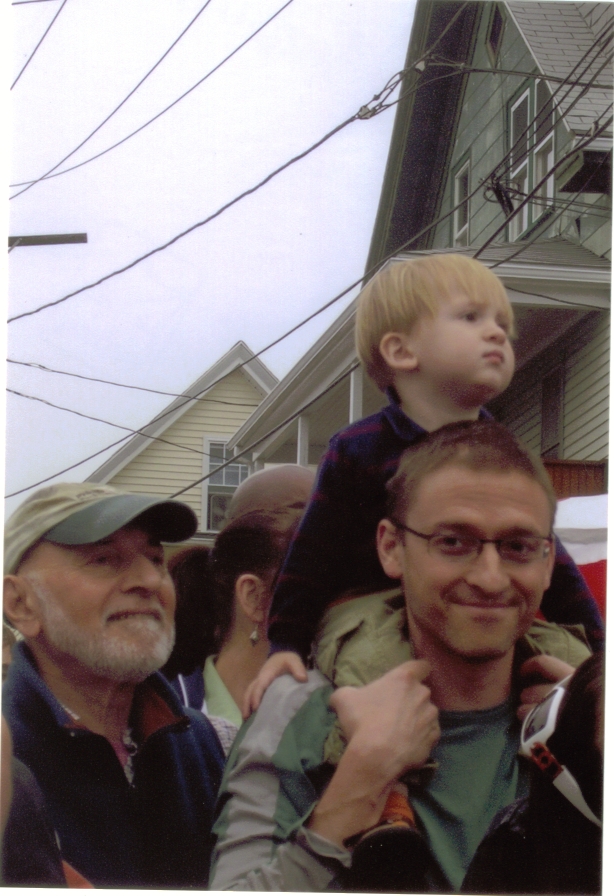

It was June of 2009. My son Ben and I were taking his 19-month-old son Isaac to his first St. Peter’s Fiesta. My mother had accompanied my brother and me when Fiesta started up again after the war, and I, in turn, took Ben and his two siblings, beginning in the 1960s. If you count the fact that my mother, who was born in Gloucester in 1910, had attended the earliest Fiestas, beginning in 1927, four generations of our family have been celebrating the Feast of St. Peter with our Italian friends and neighbors.

Though a bit overwhelmed by the crowds along the midway, the music from the rides, and the amplified voices announcing games of chance, my grandson seemed to take to Fiesta. Eyes shining with wonder, he refused to be carried by his father or me, rushing instead among the legs of those on their way down Beach Court to where we could watch the seine boat races and greasy pole contest from the shore.

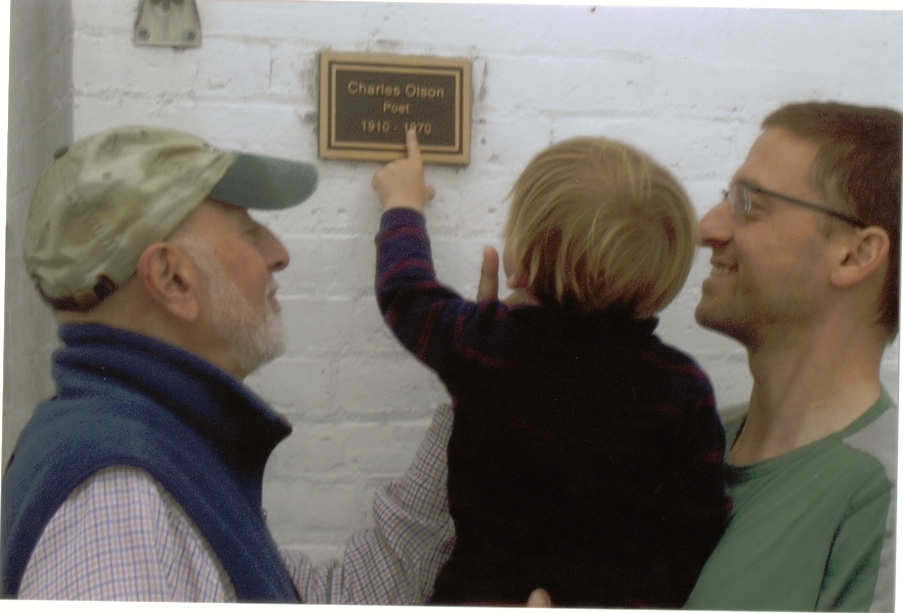

Returning to Commercial Street, we decided to walk to Fort Square for a better view of the events and so that Isaac, who loves to play in the sand boxes of Brooklyn’s city parks, where he lives, could fully enjoy Pavilion Beach. On the way there I pointed out the old Birdseye plant with its iconic white tower to Ben, where, from 1928, his grandmother had worked as Clarence Birdseye’s secretary. On our way back to Fiesta we walked around Fort Square to Charles Olson’ house, where we took a picture of Ben, Isaac and me in front of the commemorative plaque to Gloucester’s great poet.

That afternoon we covered the entire Fort, from Beach Court to Fort Square. We shared fried dough and Ben shot a few baskets to see if he could win a stuffed animal for Isaac. What came home to me during our walk, along with the powerful sense of attraction I’ve always had for Fiesta and for the Fort itself, where I once worked on fish, was an increased concern that if a proposed hotel were to be built at the Birdseye there could be unforeseen consequences. Prospective developers had already expressed reservations about this traditional marine industrial neighborhood (one was quoted in the Gloucester Times as having said, “When our guests arrive we want them to know they’ve arrived somewhere”—as if the historic Fort were nowhere!); and one wondered how many of their guests would spend a lot of money to stay in a busy neighborhood full of trailer trucks and early risers. What would be the impact of the new hotel on Pavilion beach, which was public and protected as such? And while I could imagine some hotel guests enthralled by Fiesta, would others on vacation be annoyed by the noise, the crowds, or the smells from the working waterfront—the engines of the fishing vessels, the early morning activity of taking on ice?

During our walk I tried to envision the Fort with a fancy upscale hotel in its midst. All I could think of was that the hotel might ultimately displace the neighbors, the neighborhood, the Fiesta, and all the traditional kinds of single and multi-family housing on the Fort. Once the hotel was in place, there was certain to be greater pressure for upscale housing or condos. Then, quite covertly, we would have the beginnings of Newport right in the heart of the waterfront.

I was especially concerned about the potential for “collateral damage” in the neighborhood as a consequence of outsize development, especially if traditional fishing industry businesses were pushed out, and long-term residents with them. These thoughts troubled me as I walked with my little grandson and his father—three generations of Anastases enjoying Fiesta (and a fourth if my mother, who first took me, were still alive)—and suddenly a great sadness came over me, followed by a profound sense of loss.

What should ultimately have been an occasion of joy with my family, my grandson’s first Fiesta, prompted a bittersweet reverie, in which I could imagine all that has meant so much to our family and every other Gloucester family of Fiesta and of the Fort itself, taken from us were we not vigilant about protecting our heritage and the very places in which it lives and breaths.

Today the hotel, so utterly alien to everything the Fort has stood for, is fast becoming a reality, and we can only hope that Fiesta, along with the Fort itself, will not be swept away by this new wave of urban renewal called gentrification.

Viva San Pietro!

St. Peter’s Fiesta, which opens its 88th year with music on Wednesday, June 24, at St .Peter’s Park and concludes on Sunday night, June 28, with a procession through the Fort, is Gloucester’s most meaningful celebration of our collective identity. Watching the lights and the altar go up this week and feeling the excitement in the air of impending carnival, which so many of us have experienced since childhood, I couldn’t help but remember the first time I took my grandson to Fiesta…

It was June of 2009. My son Ben and I were taking his 19-month-old son Isaac to his first St. Peter’s Fiesta. My mother had accompanied my brother and me when Fiesta started up again after the war, and I, in turn, took Ben and his two siblings, beginning in the 1960s. If you count the fact that my mother, who was born in Gloucester in 1910, had attended the earliest Fiestas, beginning in 1927, four generations of our family have been celebrating the Feast of St. Peter with our Italian friends and neighbors.

Though a bit overwhelmed by the crowds along the midway, the music from the rides, and the amplified voices announcing games of chance, my grandson seemed to take to Fiesta. Eyes shining with wonder, he refused to be carried by his father or me, rushing instead among the legs of those on their way down Beach Court to where we could watch the seine boat races and greasy pole contest from the shore.

Returning to Commercial Street, we decided to walk to Fort Square for a better view of the events and so that Isaac, who loves to play in the sand boxes of Brooklyn’s city parks, where he lives, could fully enjoy Pavilion Beach. On the way there I pointed out the old Birdseye plant with its iconic white tower to Ben, where, from 1928, his grandmother had worked as Clarence Birdseye’s secretary. On our way back to Fiesta we walked around Fort Square to Charles Olson’ house, where we took a picture of Ben, Isaac and me in front of the commemorative plaque to Gloucester’s great poet.

That afternoon we covered the entire Fort, from Beach Court to Fort Square. We shared fried dough and Ben shot a few baskets to see if he could win a stuffed animal for Isaac. What came home to me during our walk, along with the powerful sense of attraction I’ve always had for Fiesta and for the Fort itself, where I once worked on fish, was an increased concern that if a proposed hotel were to be built at the Birdseye there could be unforeseen consequences. Prospective developers had already expressed reservations about this traditional marine industrial neighborhood (one was quoted in the Gloucester Times as having said, “When our guests arrive we want them to know they’ve arrived somewhere”—as if the historic Fort were nowhere!); and one wondered how many of their guests would spend a lot of money to stay in a busy neighborhood full of trailer trucks and early risers. What would be the impact of the new hotel on Pavilion beach, which was public and protected as such? And while I could imagine some hotel guests enthralled by Fiesta, would others on vacation be annoyed by the noise, the crowds, or the smells from the working waterfront—the engines of the fishing vessels, the early morning activity of taking on ice?

During our walk I tried to envision the Fort with a fancy upscale hotel in its midst. All I could think of was that the hotel might ultimately displace the neighbors, the neighborhood, the Fiesta, and all the traditional kinds of single and multi-family housing on the Fort. Once the hotel was in place, there was certain to be greater pressure for upscale housing or condos. Then, quite covertly, we would have the beginnings of Newport right in the heart of the waterfront.

I was especially concerned about the potential for “collateral damage” in the neighborhood as a consequence of outsize development, especially if traditional fishing industry businesses were pushed out, and long-term residents with them. These thoughts troubled me as I walked with my little grandson and his father—three generations of Anastases enjoying Fiesta (and a fourth if my mother, who first took me, were still alive)—and suddenly a great sadness came over me, followed by a profound sense of loss.

What should ultimately have been an occasion of joy with my family, my grandson’s first Fiesta, prompted a bittersweet reverie, in which I could imagine all that has meant so much to our family and every other Gloucester family of Fiesta and of the Fort itself, taken from us were we not vigilant about protecting our heritage and the very places in which it lives and breaths.

Today the hotel, so utterly alien to everything the Fort has stood for, is fast becoming a reality, and we can only hope that Fiesta, along with the Fort itself, will not be swept away by this new wave of urban renewal called gentrification.

Viva San Pietro!