Main Street

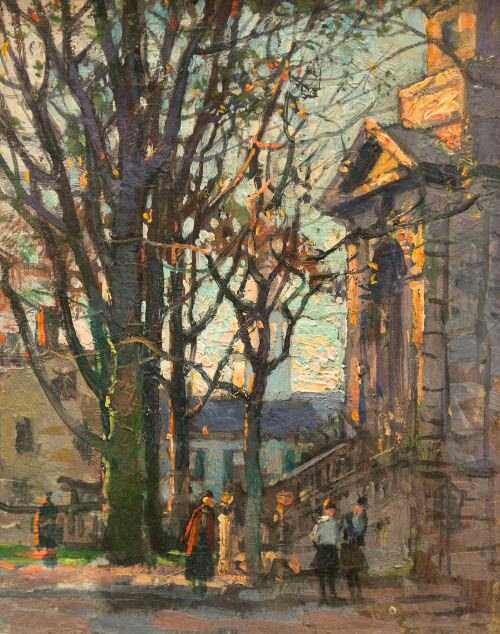

Middle Street, Gloucester. Paul Cornoyer (1864-1923)

One day I saw her, as I had during all the years past, and the next day I didn’t. Had she died? Was she suddenly in a nursing home or hospital? At her age she couldn’t simply have moved away; not her, with the sense she projected of continually having been rooted here.

Was she a retired teacher? She looked like one, had the rimless bifocals Miss Harris and most of our teachers once wore, hair in a bun. Had she been a secretary in a law office? There were many, women who hadn’t married, but who, like my mother, had gone to work out of school with typing, shorthand and bookkeeping skills they’d amply acquired in the former Commercial Course at Gloucester High School. They staffed the banks, or they clerked in the gas and electric company, as my Aunt Harriette had done all her life. They became operators in the Bell Telephone Company office building on Elm Street that later became National Marine Fisheries, where my mother also worked and is now the Cape Ann Museum’s library.

For weeks I agonized over her disappearance. I could have asked my friends in the post office who knew everybody in town. But it didn’t occur to me to ask. It didn’t occur to me to do anything but remark her absence. It didn’t even occur to me to check the obituaries in the Gloucester Daily Times, even though I didn’t know who she really was.

It got to be that way as I lived my life on Main Street during the thirty years I spent working at the city’s anti-poverty agency. Two trips daily to the post office, one to pick up my own mail at 10:30 each morning, and a second in the afternoon to post the agency’s, but more to get out of the office during coffee break, when I could afford a few minutes for a walk around town: Dale Avenue from the post office, City Hall and the library to Middle Street, then down to the Joan of Arc statue in front of the American Legion Building. Around the corner to Main Street, through the West End, and all the way back to the office on Elm Street. Soon I began to think of myself as an old Gloucester dog, making his habitual rounds; that is, before the city instituted a leash law.

On those daily strolls I came to know dozens of people by sight, men, women, natives I’d recognized since childhood, having seen them every day in Woolworth’s, Sterling Drug, the Waiting Station, all of them gone now, the people along with the places themselves: Sears & Roebuck, W. T. Grant, Gorins, W. G. Brown. Dr. Benno Broder’s dental office on Pleasant Street, with a human skull in a glass-doored bookcase; the old Western Union’s tiny dark storefront from which you could telegraph a message anywhere around the world. Willie Alexander’s father’s Baptist Church across the street from City Hall and the Museum, torn down for parking. Elks Lodge, now condos; Knights of Columbus, likewise; Red Men’s Hall vanished; Masons moved to Eastern Avenue. Bradford Building burned down, the fire in which E. E. Cummings’ Harvard classmate, painter Winslow Wilson, lost the manuscript of his autobiography. Hotel Gloucester, on Main across from Elm, where, in a small rented top floor room, I worked on my second novel—gone in urban renewal, along with the old police station and the Fishermen’s Institute, a bethel for retired mariners, who gathered to swap stories in front of the bank on the corner of Main and Duncan, or in the sun across the street at Sterling Drug.

One by one they’d disappear, like the little old lady in brown—the fishermen, the retired letter carriers, the women who sold us toys in Woolworth; those who drew the chilled root beer out of the casks at Kresge’s or measured out the penny candy.

Jake’s on Granite Street, where we bought bubble gum on the way to Hovey School, now an apartment house; Cher Ami’s ice cream parlor on Washington converted into a barbershop. Bart’s Variety on Pine and Washington streets, where we went for Italian ice, a driving school today. Captain Bill’s on Main and Washington, once Frank Barkas’ restaurant and pool room, now the Blackburn building with Giuseppe’s on the ground floor, until it, too, closed, to be replaced by a tonier Tonno.

I could see the old clapboard or redbrick buildings as they were abandoned or torn down, residents displaced. I watched them emptied of what they sold, windows gone blank. Though devoid of human habitation, the places themselves had a lingering presence; even their smells persisted—yeast from the Sunnyside Bakery, burnt almonds at Mike’s Pastry, sawdust in front of the National Butchers. But the people, like my little old lady in brown, had an equal vitality, which, as they too disappeared, slowly ebbed out of the city itself, along with the local dialect and the natives’ slouching walk, draining the city of its uniqueness and spirit, except for the young people I run into today on Middle Street. They’ll be heading home from high school, pierced and tattooed, their hair in dreadlocks, often speaking Spanish, a language I never heard until I went to Europe, or Brazilian Portuguese. Or they’re African-American. It wasn’t until I moved to Rocky Neck in 1951, and started sneaking over to the Hawthorne Inn Casino to hear jazz, that I actually saw a black person.

What would these teenagers in 50 Cent T-shirts and slashed jeans think of the skinny kid in the maroon and silver sateen Mighty-Mac baseball jacket, coming toward them from Central Grammar as he headed home down the Cut? He’s hatless and his hair, slicked down even in the autumn wind, has been cut at Bill Maciel’s barbershop on Duncan Street, next to the Fishermen’s Institute. Theirs goes wild and they wear hooded sweatshirts against the cold. They talk on cell phones, get their music from iPods, living in a digitized world that was imagined only in the science fiction novels I read at their age.

I find it remarkable that sixty-eight years later I’m taking the same route I took home from school, the route that led past the old “Y”, the Solomon-Davis house, and C. F. Tompkins’ furniture store, all since disappeared; past the Lorraine Apartments that managed to survive condo mania only to be destroyed in a fire that took the synagogue next door with it; past Pike’s Funeral Home, where my father’s and my brother’s memorial services were held and my mother’s ashes reposed before her grandchildren and I scattered them at sea; past Trinity Congregational Church, rebuilt after the fire in 1979 that destroyed the original structure, where my brother and I attended Sunday school during the war because the gas ration prohibited travel to the Greek Orthodox Church in Ipswich. When I was twelve or thirteen, had anyone predicted that I’d be walking on Middle Street, balding and gray-bearded, or told me I’d still be in Gloucester in 2018, I would have been incredulous.

But it’s not myself as I appeared then I miss, it’s the old people I grew up knowing with their sense of correctness in what they wore and how the men still tipped their hats to women on the street, asking each time, “And how’s your mutha?” Live in a place long enough and its entire history replays itself in your head. You come to know where everyone’s house is, even in childhood, where their parents came from, their grandparents. You saw their little sisters in strollers on the Boulevard or at St. Peter’s Fiesta. You went to Hovey School or Forbes with their brothers and cousins. You could tell from anyone’s face who he was, who his father was. Each beautiful blond Finnish girl in school had a beautiful blond Finnish mother who’d gone to school with your mother or your aunts. The minute you met the mother you knew who her daughter was, or her sister. Visiting Gloucester High School today, I see the great-granddaughters of my classmates and know exactly who they are, even though I can no longer remember their mothers’ names.

Live in a place long enough and it enters your dreams. There was another woman I saw one day on Middle Street, getting out of her car in such a way that I felt I was reliving a dream. She’s tiny, like my mother, and she’s Lebanese, probably related to Freddie Kyrouz, who used to run the shoeshine parlor on Main Street before he became city clerk. I know this woman from city hall, from the bank, from the post office, yet, like the lady in brown, I don’t remember her name. We always say hello and smile. And the other day when I caught the lovely clear expectant look in her eyes, her smallness like my mother’s and my aunts’, I was overwhelmed by impending loss because I realized she will become one of those people I may no longer see, one of the many who are ebbing away just as the city itself is being erased by strip mall commercial complexes, proliferating donut franchises, cheap modular houses jammed into pocket-sized lots, imposed upon us by those, as Charles Olson wrote, “who take away and do not have as good to offer.”

A bitterly contested retail complex with a mega supermarket was recently completed near the Route 128 entrance to the city. Called Gloucester Crossing and billing itself as “the premiere shopping destination on Cape Ann,” the center is competing with downtown businesses that have been struggling for years to stay afloat. Soon it will be accompanied by a 200-unit “market rate” housing complex with added retail space and a new YMCA. And on the Fort, one of the last remaining ethnic enclaves in the maritime heart of the city, a billionaire developer has built a 94-room “boutique” hotel and function center in a neighborhood where a delicate balance has long existed between residents and a thriving marine industry.

I walked sadly away after I met the Lebanese woman getting out of her car across the street from St. John’s Church, in front of the house that used to be Dr. Doyle’s office, where my brother and I were taken when we got sick or had poison ivy infections. In her persistence in my daily life, her smile of recognition, she embodies for me what my life here has meant, a connection to a single place and a sense of duration I never expected to experience when I was younger.

I don’t have to ask anyone in my generation who Pat Maranhas is, or if they remember that he played tenor sax in the Modernaires, or that his grandfather was a fisherman named Captain Green. We take people like Pat, with whom we went to kindergarten or worked with at Gorton’s or see at the bank or walking his dog in Magnolia, for granted, just as we understand why a house covered by aluminum siding should never have been put up where our junior high school shop teacher Tom Brophy’s graceful 19th century white frame house once stood on the corner of Pleasant and Shepherd streets, or why it was unthinkable to tear apart the lovely wooded, granite-bouldered, hill above Brightside Avenue and wedge a bunch of houses into it that look like they were made from kits you’d buy at Wal-Mart.

And unless they happened to be born here, who will ever know what it felt like to walk home from high school every day along the waterfront, smelling the gurry and the rendered mink food, the codfish cakes at Gorton’s cannery, and the tar and oakum caulking from the railways; listening to the screech of gulls and the idling engines of the boats at dock. Or returning home from Hovey School through the sumac bushes clustered high on Rider’s Rocks, the entire harbor spreading out beneath you, all the way to Boston. Or even Middle Street, on the way home from Central Grammar, day after day, knowing the Solomon Davis house like one’s own, the two sisters who lived as recluses in it, apparitions from the 19th century, or that the YMCA bought it for a mere $25,000 and tore it down, the city’s stateliest example of Greek Revival architecture, for a concrete basketball court that was never built. Or the Parsons-Morse house on Western Avenue, another of the North Shore’s endangered First Period houses, which Olson fought to save but couldn’t, torn down by the state to widen the highway that never got widened.

They wouldn’t know that if you walk to the post office through the parking lot behind City Hall, even on the hottest day in July, there is always a cool breeze; and if you choose the same route in the dead of winter, an icy wind hits you in the face and makes you shiver even in your warmest fleece jacket.

What about sitting in the Miami Pastry Shop, later Mike’s, among the fishermen speaking Sicilian, sipping the first espresso that was sold in town and eating a ricotta pie that one could not find the equal of in the bakeries of Boston’s North End?

And what of the smells and tastes that Proust insists are primary? There were the strips of salt cod we pulled off the big fish drying on the clotheslines outside my grandmother’s house and ate like potato chips, and the taste of anise cookies our Italian friends’ mothers baked at Christmas. There was the smell of the grass on the river bank after it had been mowed and the sickly sweet perfume of clethra, or the flowering locusts in June, which the fishermen could smell offshore, on their way in from a trip: When the locusts are in bloom the fish come home. And always in Gloucester, the smell of fish—fish cooking and fish rotting—and the salt air off the ocean often combined with the rank smell of kelp.

In remembering these things I don’t intend to be nostalgic. I mistrust nostalgia because it’s usually not about things that no longer exist—lost people, customs, ways of being—but about yearning for those things we thought we possessed but only imagined we had; and everyone will have a Gloucester of his own, no matter when they came or left. I’m only recording what I remember of daily rhythms, of the names of people who still come to me in my dreams, of the ways these people who inhabited each neighborhood, even their dogs and cats, become so deeply embedded in our consciousnesses we can’t even articulate them, we just feel them in our blood.

There are expectations, or there were, of how each day would be, who you’d meet, who would tell you a story about whom, who would have lived next door or down the street at a time when hardly anyone ever moved, when moving was a momentous event; who would have gotten sick or died and was laid out in the family parlor, like Barry Clark’s grandmother, or little Joey Nicastro, who died in second grade from “ammonia,” and was one day in the neighborhood, reading Superman comics with us on my back porch, and the next in Addison Gilbert Hospital and then, when we saw the ribbon of black cloth pinned to his front door, lying with a suit on in a small coffin in his living room with the women in black all around him saying the Rosary and the men, home from fishing, consoling his father in the kitchen.

Don’t believe for one minute that having grown up and lived in a small town we had seen nothing of life. We came upon rotting carcasses of deer that lay dead in the woods; saw our friends’ sisters naked in their bedroom windows; watched half-dressed couples making love under the bleachers at Newell Stadium; heard neighbors screaming at each other in the dead of night; saw a sailor who had been beaten nearly to death along the Boulevard, where his blood remained for days drying in the cracks of pavement; knew the drunken sea captain, who always came into my grandfather’s shoe repair shop on Stoddart Lane, speaking perfect Greek even though he was Portuguese, because he loved the tarama Papouli prepared from fish row in the back room, packing it in small wooden casks to sell to the Hellenic markets in Boston. Yes, and we heard from our mothers talking together about the fisherman who strangled his wife, cut her body into pieces and ate her liver after frying it in a skillet; about the daughter who beat her mother to death with a hammer; the son who drowned his father in the bathtub; and the other son who killed his mother, cut her head off and tried to shred it in the Dispose-all.

We heard and saw these things, and more: the sutured wounds in Irving Morris’s head after he’d been attacked and robbed one night on Middle Street, while returning home with the day’s earnings from his First National grocery store; the blood all over the snow on Main Street after the city worker had his leg torn off by the snow removal machine; the body of a five-year-old Sicilian girl, who was run over by a trailer truck on Commercial Street (I wrote that story as a young reporter for the Gloucester Times), her tiny foot with its little red sneaker sticking out from under a tarpaulin the workers at a nearby fish plant had gently covered her with.

And I think we also came to understand certain moments of human vulnerability—the eager look I caught on a boy’s face as he approached the toy store on Pleasant Street with his father one Saturday morning, his excitement propelling him just ahead of his father, who was straining to catch up with him; or the other boy on his bike in Riverdale, shyly taking orders for Christmas cards door-to-door one August afternoon, who reminded me of my son Ben, who once sold them himself, and it made me think of my three children away at summer camp in Maine, missing them so much that I rushed home from my walk to sit alone in the darkened house on Vine Street counting the days until I would see them again.

Small events and moments—a teacher’s sharp rebuke, a neighbor’s reprimand if you stepped on her marigolds while on the run in war games—that stayed for years, returning again and again in the vacuum left by loss or abandonment. Comments we made that hurt people’s feelings, stupid remarks in school, pain inflicted: the Irish kid who called me “Pinocchio Nose” and pushed me off the sidewalk in front of the “Y.” And when I went home crying and asked my mother why he’d done it, she said I shouldn’t have been at the “Y” anyway with all those ruffians. I was so terrified it would happen again, not so much the shove as his remarks about my nose, which I was sensitive about, that I never went back to the “Y” until high school, when I played piano there at Saturday night dances with the Modernaires. And even when I saw that kid for years afterwards, still a bully—he was the son of a patrolman in Gloucester—long after he’d obviously forgotten what he’d said and done to me, maybe even forgotten me as I got older, my body would stiffen and I would find ways of avoiding him. I can still see his pinched face, can tell what the beanie he was wearing looked like the day he pushed me off the sidewalk; can even remember the sound of his voice, the humiliation has stayed with me that much. Why didn’t my mother comfort me, explaining to me why certain kids bullied or threatened us, instead of telling me not to go back to the “Y?”

der why I ever came back, or why I still love the place of my birth; and maybe it is about masochism, or the fear of new or unknown cities, which my children appear never to have experienced—Jonathan, at seventeen, on the road with his hardcore punk rock band—that kept me in Gloucester; or the inability to let go of family, of the place itself. We often speak of an “island mentality,” which natives seem to share, the sense of innate comfort we take in remaining in one place, a house, a street, a certain neighborhood (I’ve only lived at the Cut, in East Gloucester and Riverdale during all my years in the city), and the inability ultimately to leave Gloucester. Older people once boasted of never having “crossed the bridge,” when we only had one bridge out of town. I knew some of those people. They had never seen Boston and they apparently hadn’t needed to, their lives were that sufficient; though my mother took us often to the city on the train for shopping or to visit the museums. We drove to the Witch City Candy Company in Salem to pick up the chocolate bars my father sold in his corner store, walking its then dark streets and visiting the Peabody Museum, full of artifacts from the city’s East India trade. And we even ventured farther out to Newburyport, to Plum Island and the beaches of the New Hampshire coast. So, slowly, I began to leave Gloucester, though, as the years go by now, I want less and less to do so.

In the end, it comes down to this. In a shrinking world, when every place has either been destroyed or homogenized, when the culture, the national intelligence, has been reduced to the lowest common denominator; when the young hope only to consume the world’s goods, not yearn to know the world itself in all its particulars, or to embrace its arts and its languages, the books that beckon to be read, paintings to be seen, monuments to visit, cities to wander in at night, as I once did in Florence; in a shrinking world, we must have something, some place, to hold onto, and an ethos, related to that place, its history, and our own in it. We must have such a thing or die from the lack of it.

So that little old lady in brown I knew without even learning her name is even more precious to me now. For a long time I could count on her presence in Gloucester, in my own life, just as I could count on the presence of my father, my mother and my brother, who are dead now; or Charles Olson, who showed me how to know the place we inhabit through an immersion in its history; Vincent Ferrini, who first taught me about poetry; or John Rowe, the eighty-year-old carpenter on Perkins Road, who, as a child, I watched as he slowly rebuilt our front porch, hour by hour, day by day, plank by plank; patiently, carefully, purposefully, and not without delight, addressing the task, as I myself have finally learned how to write.

Now, I fear, we have come to an end of rhythms, of traditions and folkways, at least as I’ve known them; an end, too, of expectations, though the ocean remains and the seasons return, however more unpredictably. Toward the end of his life, Olson said that a writer has two choices: you either oppose the destruction of the things you love or you describe the tragedy of their loss. I’ve tried to do both, often with mixed results, but in the end, it is the loss that has remained with me, touching every aspect of my thought and being. The only Gloucester that exists for me now is the city of my mind.

(This is the first chapter of Peter Anastas’ recently completed memoir From Gloucester Out)

Peter Anastas, editorial director of Enduring Gloucester, is a Gloucester native and writer. His most recent book, A Walker in the City: Elegy for Gloucester, is a selection from columns that were published in the Gloucester Daily Times.

Peter Anastas, editorial director of Enduring Gloucester, is a Gloucester native and writer. His most recent book, A Walker in the City: Elegy for Gloucester, is a selection from columns that were published in the Gloucester Daily Times.

No comments:

Post a Comment