I wanted to be a writer like George Konrad

or Cesare Pavese, a writer in the European manner, who was both an artist and

an intellectual; a writer, who was also an outsider, as both Konrad and Pavese

seemed to be, writers who had become internal émigrés, or who had otherwise lived

on the margins of society, yet whose insights, emanating from the core of their

alienation, entered their fiction.

All during my undergraduate years and

afterward in Italy, as I walked the streets of Florence at night, trying to

picture what the city must have looked and felt like to Dostoevsky, who lived

there while writing The Idiot, or to

native writers like Giovanni Papini or Vasco Pratolini, I imagined myself

becoming such a writer, someone who lived and wrote in a furnished room, as

Carlo Levi described the camere affitati

he’d inhabited in the aftermath of the Second War, first in Florence and later

in Rome, in his novel The Watch, and

as I knew those rooms myself; someone who wrote far into the night, surrounded

by books, or who roamed the darkened streets of a still wakeful city, engaging

the night people—prostitutes, baristas who intuited at a glance what you were

seeking, students smoking and talking politics in half-lit cafes--returning to

sleep until noon before taking coffee and a roll for breakfast at a nearby bar

and then returning to work.

Between 1959 and 1962, I lived this way,

like Rilke’s Malte Laurids Brigge or an impoverished student in a Strindberg

novel, in furnished rooms on shadowed streets and alleys, rooms that looked out

over other rooms nestled under red-tiled roofs; rooms I left only to eat and

teach or to attend lectures in philology and Medieval literature at the

university, in Piazza San Marco. I can

picture them all now: the first room I had on Via Cavour, in Pensione Cordova,

when I arrived in Florence, small and neat with a desk by its single window;

and then the bright, sunny room in Piazza San Marco in the house of the

DiMaggio family, a room that looked across a courtyard to the Duomo, a

courtyard into which flocks of swallows plunged before nightfall, as the voices

of children echoed off the stuccoed walls and wash hung out to dry from

innumerable balconies. After that I

moved to Via dei Servi, renting a room frescoed with gorgons and swans, whose

double French windows I could lean out of to see the fountains of Piazza

Santissima Annunziata splashing on a summer afternoon. And finally, I lived in Via dei Fossi, off

Piazza Goldoni and the Arno, in a painter’s studio still smelling of turpentine

and linseed oil.

I’d had a room of my own, too, in

Settignano, in the Villino Martelli, on Via del Rossellino, which my friends

from Brunswick, Maine, novelist Peter Denzer and his painter wife, Ann Sayre

Wiseman, had taken in September of 1960 and invited me to share with them and

their two children, Kiko and Piet. I

loved that room on the third floor, at the very pinnacle of a narrow stone

staircase, where I slept in a 16th century carved wooden bed on a

straw-filled mattress and wrote at a little oak table by the lone window that

looked out over the Arno valley and the city of Florence below. This was the room in which I worked on my

first novel, “From What Bone,” a room with a blood-red tile floor and yellow

ceramic wood stove that heated it in chilly early mornings or on frigid Tuscan

winter nights, when I often woke to the mournful shriek of the Brenner Express,

as it departed Florence for Munich. I

cherished the solitude that was mine, once I had bid Peter and Ann good night

and ascended those stone steps to the summit of our small stucco covered house

that was flush with the hilly street, which led up from the village, where I

took the No. 10 bus daily to work or to attend lectures at the university. But though I enjoyed living in the Tuscan

hills, walking daily on old dirt roads that bordered olive groves and grape

arbors, taking coffee in the local Casa del Popolo, where Peter and I would

argue about politics with the village communists, I never felt truly myself

until I had moved back down into the city to be closer to work, and from where

I could resume my wanderings through nighttime streets, returning always to a

quiet room, where I’d have the radio softly tuned to an all night jazz program

that came from the U. S. Military Radio Station in Germany. Accompanied by the music that seemed

unerringly to fit or enhance my mood, music that reminded me of the country I

expected never to inhabit again, I would write or read until dawn.

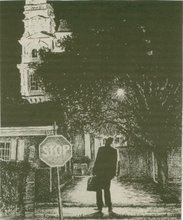

Although that need for a room of my own had

begun in high school, when we moved to Rocky Neck and for the first time I had

such a room, in the corner of which I would sit to read or

write, I’d actually sought such refuge when we lived on Perkins Road and I

began writing in the basement of our duplex on my aunt’s typewriter. But a white washed basement that smelled of

mildew was scarcely the sanctuary I’d envisioned; and I didn’t fully attain my

dream until senior year in college, when I finally had a room entirely to myself

at 83 Federal Street, in Brunswick, in a big white 19th century

house occupied by the chairman of the biology department, who rented out a

couple of rooms to students. My

furnished single room was located over an ell attached to the main structure. It had a private bathroom and an entrance of

its own from a set of steps in the driveway off Federal Street, next door to

the mansion where the president of the college lived.

Because my room was in a separate

wing I was undisturbed by the radios or record players of the few students, who

lived in the main section of the house along with Professor Gustafson and his

family. Once I'd lighted the floor lamp

behind the easy chair at the foot of my bed, the room was suffused with a

comforting yellow glow. Then, after

returning at midnight from my late work shift at the library, I'd put on my

flannel bathrobe and wrap a blanket around me.

Warmed that way, I could study or read for as long as I wished, which

was often until the first light. Usually

I slept until noon because I no longer had morning classes. In any event, I took breakfast and lunch

together.

To the right of my old upholstered

chair was a dark, polished bookcase with glass doors. It was there I kept the books I owned, the

poetry of Pound, Eliot and Williams and some paperback or cloth-bound editions

of the novels I was currently reading, including Women in Love and Aaron’s

Rod, by D. H. Lawrence, seven volumes of the Modern Library edition of

Proust, and Celine’s Journey to the End

of the Night. The floor against the

adjacent wall was lined with books I borrowed from the library. To the left of the single unlocked door to my

room was my desk. Over it I'd tacked a

large street map of Florence cut out of a Baedeker guide I discovered at a church

book sale. Between my desk and single

bed there was a window, and another at the foot of the bed and to the right of

the closet. Over my bed I had a Vlaminck

print of fishing vessels tied to a wharf in Normandy because its dark browns

and cerulean blues reminded me of the waterfront in Gloucester. On the opposite wall was a Rouaultesque gouache, by George Dergalis, a Greek

artist from Cambridge, whom I’d met on Rocky Neck. It was of an ancient flute player with

Byzantine beard and hair locks. A faded

Oriental rug covered most of the floor.

Between an antique dresser and the bookcase, a hi-fi console sat on a

table with cast iron legs. My collection

of ten- and twelve-inch long-playing jazz and classical albums was lined up

under it. Attached to the dresser was a

mirror that reflected my desk and the map of Florence. In the glow of my reading lamp the map

appeared to be made of old parchment.

This was the room I had lived in

since September of 1958. A single floor

duct heated it irregularly. Sometimes

through the register I could hear Professor Gustafson and his wife, who taught

high school English in Bath, talking quietly over dinner. My typewriter and typewriter table were

nestled to the left of my desk under the big window. The sound of trailer trucks late at night on

the Bath Road told me I wasn't isolated from the commerce of highways; and the

roar of jet planes taking off from or landing at the Brunswick Naval Air

Station, a mile from the campus, reminded me that I was never very far from the

instruments of war and those who operated them.

It was in this room, exclusive of

the roommates I’d shared living arrangements with for the previous three years,

roommates whom I liked but whose constant presence I felt stifled by, that I

began to undertake the kinds of reading and writing that I would pursue for the

rest of my life. It was also in this

room that I embarked upon the first systematic self-examination I had hitherto

pursued, as I immersed myself in the writings of Freud and Jung, an inquiry

that began by attempting to address the sense of alienation I have already

described.

I’ve mentioned George Konrad and

Cesare Pavese. As an undergraduate, I

knew nothing about the work or the existence of either. Konrad’s haunting first novel, The Case Worker, was published in 1969,

though it didn’t appear in English until 1974; and I didn’t read my first

Pavese novel, the pitilessly neorealist Il

Compagno, until I arrived in Florence, although I bought it in Rome as soon

as I’d arrived in Italy, having been told by my printmaker friend Emiliano

Sorini, whom I’d met on Rocky Neck the summer before I left for Italy, “If you

love Moravia, you will die for Pavese.”

So it was Lawrence whose essays,

novels, poems and stories I first read in that room at 83 Federal Street;

Lawrence and Hemingway, whom I had begun reading in high school, not Hemingway

the big game hunter and sports fisherman, but Hemingway the expatriate, the

young writer of the Paris years. And I

read and re-read Sartre, having discovered his writings during my freshman

year--the Chemin de la Liberte` novels, Nausea, the New Directions edition of which I was to carry with me

to Europe, and Being and Nothingness. Of Simone de Beauvoir I had only read The Mandarins. But that novel introduced me to the

highly-charged atmosphere in which Sartre, Camus and the other French left-wing

intellectuals I admired lived, the Paris of cafes and political soirees, and a

Europe that was attempting to reconstitute itself politically and

intellectually after a devastating war, a war that left many of its finest

minds bereft of hope for mankind’s future.

I read Beckett, too, and Marguerite Duras, Nathalie Sarraute, and

Robbe-Grillet, all of whose works I had first been introduced to in the pages

of the Evergreen Review, which I devoured as soon as each new issue arrived in

the mail. It was in the Evergreen Review

that I also discovered the short stories of Michael Rumaker, “Exit 3” and “The

Pipe.” Rumaker had been a student of

Charles Olson’s at Black Mountain College.

Though it would be years before we met and became friends—after Olson’s

death, in fact—Michael’s stories, later collected in Gringos and Other Stories, had a profound impact on my own fiction.

Lawrence, the working class

intellectual, who was alienated both from his own class and from the culture he

grew up in, along with the literary society that should have provided a

sustaining environment, attracted me deeply, not only as a writer but as a

person, restlessly moving from Nottinghamshire to Germany, from Italy to

Ceylon, Australia and the American Southwest, ultimately dying in the South of

France. The Lawrence who also interested

me was the Lawrence who wrote, “At times one is forced essentially to be a

hermit,” adding: “Yet here I am, nowhere, as it were, and infinitely an

outsider.”

My deep study of Lawrence in that

room on 83 Federal Street prepared me for the senior thesis I was expected to

submit as partial fulfillment of the graduation requirements for an English

major. I chose to write mine on The Plumed Serpent, not one of

Lawrence’s most successful or highly acclaimed novels, but one which interested

me because of its mythic substructure.

For as a student of Dante I was also interested in myth and symbol and

the creation of anagogic structures of belief.

There were many teachers at Bowdoin

whose courses in literature, philosophy, Latin, Greek and Italian, sustained

me, along with their friendships, making it ultimately worthwhile to have

chosen this small liberal arts college on the Maine seacoast over a major

university like Harvard, where, I feared, I would have been overwhelmed

socially and academically. But the

principal education I received at Bowdoin was not in the classroom, nor was it

at the hands of my fellow students, whom I gradually separated myself from. My true education emanated from

the Hawthorne-Longfellow Library, where for four years I read widely on my own,

irrespective of course syllabi or graduation requirements, especially during my

final two years in college, when I worked nights at the circulation desk,

studying in the library and familiarizing myself with its immense

holdings. Each night after work I would

return home with a new book, which I would read often until dawn. There was never a book I sought or needed

that wasn’t already in the stacks or in the rare book collection that contained

copies of most of the major avant-garde or underground books of 20th

century art and literature, bequeathed to the college by an alumnus and rare

book collector, Robert L. Swasey, scion of Warner & Swasey, a leading

machine tool manufacturer in Cleveland.

If, in a book about Hemingway and

the Spanish Civil War, I came across the name of novelist and historian, Arturo

Barea, I could rush to the library and find his autobiographical trilogy, The Forging of a Rebel, whose dense,

lyrical prose brought to life the young writer’s coming of age against the

background of a nascent civil war. It

was a heavy volume, bound in yellow cloth, gathering all three books of his memoir,

The Forge, The Track and The Clash, as translated by Barea’s wife

Ilsa. I remember sitting over it for

hours on a long winter night, utterly absorbed in Barea’s descriptions of his

childhood and youth as a student.

Reading Barea led me to Gustav Regler’s autobiography, The Owl of Minerva, and from Regler I

read backwards to discover seminal Weimar and Austrian writers like Hermann

Broch and Robert Musil, plunging deeply into British translations of their

great novels, The Sleepwalkers and The Man Without Qualities. Along the way I discovered Salvador

Dali’s strange novel, Hidden Faces, which

I gobbled up, along with Elio Vittorini’s In

Sicily, Kenneth Patchen’s privately printed The Journal of Albion Moonlight, Henri Barbusse’s Under Fire, all part of the Swasey

collection; and then, from the main stacks, Herbert Gold’s The Man Who was not With It and John Clellon Holme’s ur-Beat novel, Go!, published five years before Jack

Kerouac’s On the Road. Some prescient librarian or astute faculty

member had had the sense to purchase or recommend both Gold and Holmes, now

sadly neglected.

The books piled up around my easy

chair—Edward Nehl’s three-volume composite biography of Lawrence, Broch’s

infinitely complex and experimental The

Death of Virgil—and I read and read, circling around schools, eras, places,

cultures, until I had created for myself a better picture of the birth of

European Modernism than I would ever have received had I taken a course in the

subject, which wasn’t offered anyway.

The fiction I was writing at the time, stories about growing up in

Gloucester, didn’t directly incorporate this reading, but I am certain the

reading inspired it, particularly Musil’s electrifying coming-of-age novel, The Confusions of Young Torless. Mostly I wrote about what I was reading in a

journal that I began to keep, inspired by André Gide’s journals, and in daily

letters to my girlfriend Cynthia Brown, who was studying literature at Boston

University. Sadly, those long, soulful

letters Cynthia and I exchanged during that period no longer exist.

The Swazey collection was of

particular importance for me because it contained most of the published works

of Henry Miller, not only Tropic of

Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn,

in the original Obelisk Press editions, as published in Paris in 1934 and 1938

by Jack Kahane, but the privately printed The

World of Sex, The Books in My Life,

and, The Colossus of Maroussi, one of Miller’s greatest books

and of utmost significance to me as a young writer of Greek-American extraction,

planning his first trip to Europe. Exile

and expatriation had emerged as significant themes for me from when I’d first

started to read about the Lost Generation in Malcolm Cowley’s Exiles Return and John Aldridge’s After the Lost Generation. Thereafter, Miller’s own saga of abandoning

New York, followed by years of penury and artistic struggle in Paris,

culminating in the publication of the Tropics,

his life-affirming stay in Greece just before the war, and his return to travel

in America, as chronicled in The

Air-Conditioned Nightmare, were an enormous inspiration to me, both as a

writer and prospective traveler. I will

never forget the long nights during which I read Miller’s forbidden books,

books I’d spirited out of the collection late at night, only to return under

cover the next day, giving myself a single night alone to read them lest their

absence be noted.

Why do I tell you all this? Why do I share with you the titles of the

books I read in those intense months, in that single room on Federal Street in

Brunswick, Maine, while my classmates were dating girls, drinking beer, and

planning the careers that would eventually bring them more money than I would

ever earn in a lifetime of reading and writing?

Why recount the story of a lonely student, an outsider and a misfit, who

was happiest reading late at night in the yellow glow of an old lamp, as he sat

wrapped in a sweaty bathrobe in an unheated room? Who cares today about an undergraduate and

his reading habits, about a studious young man who didn’t study much but read

instead so that, in effect, he became The Self-Taught Man of Sartre’s Nausea?

Has my life changed today, sixty

years later? Am I any different from

that bearded boy in the old bathrobe, reading in a fraying chair under the glow

of a rickety floor lamp, on the corner of the Bath Road, as trailer trucks

roared by in the night and jet fighter planes took off at dawn, while I was

falling asleep, my head full of images from the books I’d read myself to sleep

over?

What I’m trying to relate, I

suppose, is not just the story of the books I read and the room I read them in,

a room that became imbued with my own perspiration to the extent that I could

still smell myself in it as I packed up to leave after graduation in June of

1959. It’s the story of my

self-education, I’m driven to share, an education that would not have been

possible without the library that contained those books and the room in which

to read them, apart from the noisy dormitories and liquor spewed fraternities

(not that I didn’t drink, and drink a lot). I don’t fault the dormitories,

though I moved out of them, or the fraternity I regretted joining and whose

membership I ultimately rejected—they were part and parcel of the atmosphere of

college in the 1950s; but they were not my Bowdoin. After three stumbling years, I had found my

own refuge to read and write in, and that refuge, if even for one year alone,

constituted the most important part of my education. It was a pattern I would follow for the rest

of my life, which, you might say, has been a life spent in small rooms of old

houses, reading and writing. For this is

the story of my life, or at least a significant part of it, and not to share it

in some detail would be to misrepresent the record of that life, insignificant

as it may seem.

I attended class during those years

I’m speaking of and I did pretty well in most of my courses, reading Dante and

Sophocles in the original, immersing myself in Romantic poetry and ancient

history, making dean’s list and graduating with honors in English. I had a girlfriend, as I’ve said; I went to

parties, though I spent most of my time playing piano at them and in other

venues around Brunswick. But my room at

83 Federal Street meant more to me than anything else.

I’ve studied with great

teachers. I first learned how to read

and write critically with Hortense Harris at Gloucester High School. At Bowdoin I studied expository and

imaginative writing with novelist Stephen Minot, and literature and criticism

with novelist and Hawthorne scholar, Lawrence Sargent Hall, while under Walter

Solmitz I began my lifelong study of philosophy. I continued to read Dante and I studied

Romance Philology in Florence with Domenico De Robertis. I attended lectures on Renaissance culture by

Eugenio Garin and I audited classes on contemporary European literature by

Mario Luzi, both major scholars at the university, and Luzi himself a

distinguished contemporary Italian poet.

In graduate school, at Tufts, along

with reading Shakespeare with Kenneth Myrick, I studied

Milton’s poetry and prose with Michael Fixler, whose Milton and the Kingdoms of

God is one of the seminal studies of the poet as Christian theologian. At Tufts I also began, under the tutelage of

Americanist Wisner Payne Kinne, the deep immersion in the books and essays of

Henry David Thoreau that would lead both to my thesis on Thoreau and the

phenomenology of place and to a lifelong absorption in the writings of the

Concord seer whose words and whose politics guide me to this day. All of these teachers made a profound

impression on me, opening me to the richness of their own minds as well as to

disciplines I might never have been able to master on my own. But at bottom, and certainly due to their

guidance, I have essentially become my own teacher.

I’ve lived and written in other rooms. Upon my return from Italy I rented a studio

at the Beacon Marine Basin on East Main Street, high over Gloucester harbor,

where I completed a second novel, and where my wife and I lived before moving

to a carriage house on Farrington Avenue, bordering Eastern Point. It was there, in a quiet back room that later

became my first son Jonathan’s bedroom that I wrote my master’s thesis on Thoreau

and the short stories that would become my first publications. From there we moved to an 1850s farmhouse on

Vine Street, in Riverdale, where I had a study overlooking Gloucester’s oldest

intact colonial dwelling, a meadow rich in wildlife, and Ipswich Bay. Here I wrote another novel, “Reunion,” a

memoir, Landscape with Boy, and my

first two published books; and it was here that I remained living and writing

alone for many years after the end of my marriage.

When my landlord died and the

property went on the market, I moved from Vine Street to a house in Bickford

Way on Rocky Neck, overlooking Wonson’s Cove.

In a tiny first floor room, flooded with light for most of the day and

with a view out onto the cove, I finished At

the Cut, my memoir of growing up in Gloucester during the 1940s, and No Fortunes, a novel about my final year

at Bowdoin, while also completing most of Broken

Trip, a novel-in-stories about Gloucester in the 1980s and 90s, published

in 2005 by writers Grace Paley and Robert Nichols of Glad Day Books.

I’m writing this in my study on Page

Street above the ocean, far up on Mt. Pleasant Avenue from Rocky Neck,

surrounded by the books I began collecting when I lived on 83 Federal Street;

but I come back to this room and that time, where it all began, and where I

often feel it was better than in any other room or in any other time or place

in my life.