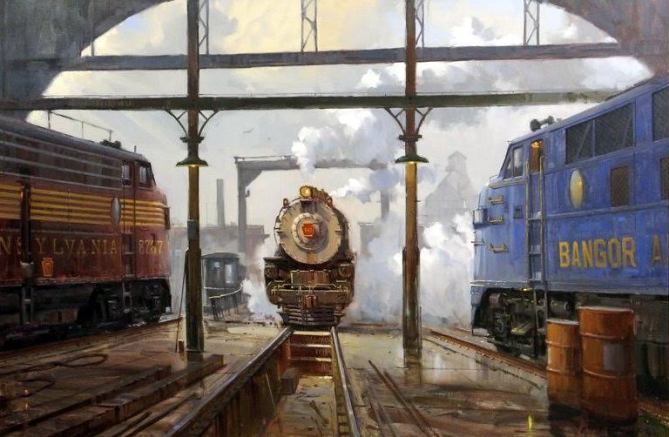

Showdown at Roundhouse Corral, (Boston Railyard) © 2000

David Tutwiler (b. 1952)

David Tutwiler (b. 1952)

I come from the era of trains. As a child during the war, I would lie in bed on Perkins Road listening to the shrill whistle of the Boston & Maine’s Gloucester Branch crossing the trestle over the Annisquam River. Ever since then I have associated trains with the mystery of travel. I could never get enough of them, pestering my grandfather Angel Polisson to take my brother and me to the station in Gloucester to see the trains arrive. I especially loved it when we could watch the passengers getting off and I could only imagine where they had been or where, if the train was about to depart, they might be headed.

As we got older, our mother took us to Boston on the train, when she went shopping at Jordan Marsh’s or Filene’s. I’ll never forget the time I got separated from her in Filene’s basement. I went screaming up and down the aisles of bargain clothing piled on tables that women fought over, cursing each other, sometimes tearing the garments to shreds in their furious attempts to possess them. After that incident, my mother took to pinning a name tag on my brother and me, so that if we got lost or separated from her the clerks would know whom to page. Luckily, it never came to that, and we quickly learned how to navigate our way around the big department stores, or the Peabody Museum in Salem, where our mother also took us so we could look at the ship models that fascinated us, or the life-like local birds and mammals that the taxidermists had exhibited in large glass cases.

Recently I thought of those cities I came to know in wartime when the gasoline ration prohibited travel by car—Boston, Salem, even New York when we got older—and the trips on trains it took to get to them. I was on the train to New York again, racing along the Connecticut coast, in and out of harbors and across russet colored fields on the way to see my new grandson in Brooklyn. The train was packed, the early spring day was bright, and I felt like a child again on an adventure.

It was the way I felt in Europe, where I took the train everywhere, never thinking of schedules or reservations. If you wanted to go somewhere, you showed up at the station and there was a train waiting or about to arrive. One night a group of us were sitting over dinner at the Buca Niccolini, on Via Ricasoli in Florence, just behind the Duomo. It had been a grand meal, well moistened with the local red wine the Florentines call “vino nero.” We were about to order desert when someone suddenly suggested, “Let’s go to Vienna for desert!”

We jumped up, settled the check and set out for the railroad station, a short walk from the restaurant. The Brenner Express was about to depart. We knew we would never get to Austria for desert, but we did arrive in time for one of those marvelous Viennese breakfasts. We took a spin around the city and got back on the train, arriving in Florence in time for dinner.

Naturally, this was the kind of gambit you engage in when you are young—we were in our early 20s, students: Americans, English and Italian. I never did it again, but I took the train at every opportunity—to Bologna for lunch (best pasta ever); Pisa for a run up the steps of the Leaning Tower with my high school classmate Bob Stephenson; Viareggio to get my beach fix when I missed Gloucester.

Trains were even more important for me before I lived in Europe. I went to college in Maine and most of the time I took the train to Brunswick or back home. I’d hop on a Gloucester train to North Station, where the Flying Yankee left for Portland, Bangor and points north. There was a club car serving beer and other alcoholic beverages all the way to Portland, where it was uncoupled before the train left for Brunswick. On many a night we could be seen stumbling up to our rooms from the Brunswick railroad station.

At midnight the mail train stopped in Brunswick, allowing those who had girlfriends in Boston to post letters that would be delivered to them that morning. I can see myself hastily typing a letter, throwing on parka and boots, and trudging through the snow from my room on Federal Street down to the railroad station on Maine Street, often getting there just as the train was about to pull out. The guys in the mail car knew us. Obligingly, they would lean out of the doors to accept our letters on the fly.

At four a.m. every morning the Milk Train coming through from Northern Maine to Boston woke up those of us who lived near the railroad bridge on Federal Street. If I was reading or studying late, I knew that its whistle in the dead of night was the sign for me to go to bed. But the big event of the day was the non-stop rush through Brunswick of the freight train. Imagine an engine pulling 100 or more cars all the way from Aroostook County tearing through the center of town, the late afternoon traffic sometimes halted for close to 30 minutes. Our philosophy professor told us that if we still believed in the non-existence of un-thinking matter we should stand next to that freight train as it roared through town each afternoon.

While some students had their own cars, most of us depended on the train for a fast getaway to Portland to see a movie or to eat Chinese food. Often enough we traveled north to Rockland, and sometimes further Downeast, stopping at Wiscasset on the way to Rockland, Camden or Belfast. There was something special about Wiscasset, a sense of arriving in a small riverine town with redbrick buildings, the train pausing, it seemed, until the very last passenger appeared out of the dark, the conductor waiting with his lantern and finally shouting, “All aboard, all aboard,” as the train pulled slowly out of the station. I can still hear the chugging of the steam engine, the way the wheels clicked on the tracks, and the eerie whistle as the train plunged into the darkness.

It is the image of that night train at Wiscasset Station that remains with me above all others, a sense of the isolation of the station itself and the deserted town, the slowly diminishing sound of the whistle and the rhythmic clicking of the wheels on the tracks, the lights from the cars gradually becoming bright points in the darkness and then disappearing altogether as the train itself faded into the night. It is an image that takes me back to the boy awake in his bed on Perkins Road, listening attentively each time for the train to cross the trestle over the river, imagining what it might be like to travel on it, to arrive in unknown places, connected only by the trains themselves, the infinite network of tracks, as they raced through the vast spaces of the night.

Peter Anastas, editorial director of Enduring Gloucester, is a Gloucester native and writer. His most recent book, A Walker in the City: Elegy for Gloucester, is a selection from columns that were published in the Gloucester Daily Times.

Peter Anastas, editorial director of Enduring Gloucester, is a Gloucester native and writer. His most recent book, A Walker in the City: Elegy for Gloucester, is a selection from columns that were published in the Gloucester Daily Times.